Chris Holder: An Argument for Early Specialization in Sports

I might be the only person on the planet who thinks this way, and I’m okay with it. If you are at all involved in athletics, on any level, the topic of specializing too early will inevitably be brought up.

When is it too early to start focusing on one sport?

What types of dangers do I expose my child to if I let him/her move into the one sport mentality too soon?

What obstacles are we going face if I give into letting Jimmy or Jane become a one sport athlete?

Real concerns for a time in our history where early specialization is becoming the norm.

The argument against early specialization is a strong one. There are a myriad of real concerns that can make it a bad idea to take your kid out of their gymnastics class and away from their travel basketball team for the purpose of focusing on baseball alone.

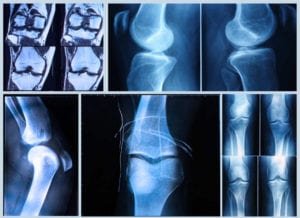

Speaking of baseball, much of the momentum for the anti-specialization mentality is a product of young pitchers throwing their arms to smithereens before they get to high school. Tommy John surgery for teenagers and the development of big-league shoulder issues before the need to shave are both very compelling motivators to shy away from letting little Johnny work to becoming a full-time baseballer.

The CTE nightmare is the latest in the list of reasons as to why to keep your kids involved in multiple sports. The problem with this line of thinking is that CTE and the other problems that can arise from multiple concussions are not exclusive to football. If you understand that this is an accumulation of head impacts and not one big event, you realize that although the chance of head traumas are most likely to occur in football and combat sports (MMA, wrestling and such), this is going to happen in most every sport where contact is a reality. I have been working in the university athletics setting for nearly two decades now and we have as many volleyball, basketball and soccer athletes in the sports medicine room sitting out because of concussions as we do football kids. Per capita, it’s nearly 1:1.

The last, and perhaps most compelling argument to me is the idea of burnout. The primary reason I say this is because at the level I work, we are seeing the ramifications of kids who are 19-20 years old who have been playing their sport for up to 15 years and they are just over it. The “love” is gone and many of them are here because they want to keep their scholarship and they have a skill set that keeps them relevant. I would venture to guess that more than half of my athletes (and we are talking over 500 where I work) would tell you that they are pretty much ready to move on.

I know this all too well because I was that guy when I was wrapping up my playing days. I needed to finish my degree, I had endured a list of injuries, had some surgeries and felt like an old man. By my senior year in college, I wanted it to end. I loved my school and my teammates, but I was mentally and physically done.

We are in a time where we might know too much. We know about CTE. We understand the UCL in the elbow and the mechanical challenges that a pitcher faces. We know about the mechanisms of an ACL tear. These are all things that parents need to consider as we move to a more one-sport way of thinking. But that same argument, “We know the dangers, we see it happening and avoidance is the only smart approach,” works the other way as well.

I would venture to guess that there is no industry in the last 20 years, besides perhaps cell phones and computers, that has made bigger strides and advances than that of strength and conditioning. What we have now, versus what I had (I played my last snap in 1999), is not even the same conversation. It’s a perfect example of apples and oranges. What we recognize as standards of practice compared to what my coaches were trying to do aren’t close to one another, even though the intention was the same: Get’em fast and strong, help prevent injuries and do what is needed to give them a chance to win.

This is where we solve our problem with specialization, at least the physical concerns. We are also an industry of “follow the leader.” The hive mentality of strength people, personal trainers and performance coaches is almost comical. Even though many of us like to posture around one another (go to any NSCA event and watch the squaring off that happens), we all do the same things. Everyone squats, everyone deadlifts, everyone bench presses, everyone does the Olympics . . . I know this might sound like I am taking a swing at my community, but what I’m really doing is tipping my hat to them. My peers are some of the smartest people around and what we have done in the last 20 years, as a hive, has been to become incredibly effective thinkers. Our programming of the old standards is now true science. Gone are the days of squatting till you puke (yes, I’ve done those workouts). We have systematically learned to think like doctors and physical therapists as we prescribe our lifting programs.

With this in mind, let’s look at a normal volleyball family. You have a freshmen in high school who wants to go on to play college volleyball. Many of you reading this know what I’m talking about. By the time these girls get to high school, they have specialized—because they have to. The life of a volleyball athlete is truly a grind, perhaps more than most of you understand. The calendar year is full for a young volleyballer. In late November, early December, club volleyball tryouts begin. This lasts for a couple of weeks, teams are established and club practices begin. Many of you are saying, “Club? Who cares about club?” If you are saying this, you don’t understand how recruiting works. Club, for volleyball, soccer and AAU basketball is where the college coaches go to recruit. Not high schools. This girl will get a short break for the holidays, and once the New Year rolls around, we are in full club season. Tournaments start and this will go on until late May. If her team is good enough, they will make Junior Olympics (JOs) and this season will carry into the middle of the summer.

Regardless of JOs, most high school volleyball teams begin try outs in late June. Again, once the teams have been determined, the kids who made it will start high school practice immediately. Games begin in late August/early September and the season will wrap up in November. Then, club try outs begin and the cycle starts over. Throw in dozens and dozens of individual and coaching personal sessions that all of these kids do (to get ready for try outs and work on skill development) and what you have is a teenage athlete who never takes a break from their beloved volleyball. It’s a massive industry and club directors and organizations are making a ton of money operating this way. Because of the level of showcase they can provide for an athlete (exposure to all universities during club tournaments), these kids have to do it this way. In all my years of coaching in the college ranks, my volleyball coaches say that this is how it’s done. What might be even more frightening is unlike football and some other sports, volleyball players commit to their chosen university by their junior year in high school. If you haven’t signed with a school by the end of your junior year, it’s because you probably aren’t good enough to play at that level. This means that the clock to develop a high level volleyball athlete is actually shorter than that of many other athletes.

The solution to many of the problems with early specialization lies in a dedicated, well thought out strength and conditioning program. We are too far along now for a year-round athlete to not have a working, systematic strength program to keep the surgeon away. Repetitive motion sports like swinging a bat or golf club, throwing a ball, all swimming strokes and hitting (as in volleyball) create patterns in the nervous system of an athlete. The brain is constantly trying to regroup the way the body approaches a task in order to make it easier.

This is a double-edged sword and is the lone reason the truly talented reach their full potential (the idea behind the 10,000 hours to mastery concept). It is also the reason most of the rest of us end up broken.

If you need an example, look at a swimmer’s body or at how a golfer stands. The swimmer will have pulled forward shoulders nearly 100% of the time, and the golfer, when standing neutral, will have a bit of a turn at their shoulders (as if twisting near the top). These are anatomical changes the brain has made to give this athlete an edge, easing them into the postures and positions of their favorite sport.

Great for their athletic tasks, but not as good for everyday life . . . all in the name of efficiency.

For my parents reading this, you have a new list of concerns. I’m a father of three young kids who all love playing sports. What do we all want for our kids? Ultimately, we want them to be happy. But our concern is for the long haul, not for just the first 25 years of their lives. We want them to feel good, we want them to be healthy and we want them to live a long, pain-free life. With the way the system is set up as we know it now, we, as parents, must realize that it is in our hands to make sure that our kids get the opportunity to have tremendous athletic success in their chosen sport, and not beat themselves down so their bodies wear out long before the should.

I understand that adding more to an already full plate seems counterproductive, but I can assure it is not. Having a smart strength routine will fortify their bodies and help them combat the repetitive stress that being a one-sport athlete imposes on a kid. Most of our children succumb to some chronic stress/repetitive motion injury because the second they leave the field, gym or pool, they do nothing to restore themselves. They pick up their phones, park their butts and allow the stimulus from practice or a game to set in . . . and repeat. Over and over.

They need to get their behinds in the gym. They need full-body movements that combine great technique with appropriate loads. They don’t need to have the mentality that every time they enter the weight room they need to lift the world, or grind until they are a wet mess sprawled out on the floor. There will be a time for all of that. Smart strength training is about creating balance. It’s about developing coordination throughout the entire system, and it’s done in a very linear way where the body adapts to basic human functions—bending, squatting, pushing and pulling. They need to understand that all the back work they are doing is to help combat all the throwing or their swimming stroke, not to give them a huge lat spread. They need to understand the reason they are squatting isn’t just to build tree trunk legs but to keep their glutes firing properly and to maintain healthy hip range of motion.

Strength training isn’t isolated to only getting swole.

The primary reason I am writing this right now is because I am facing this as a parent in real time. My son is nine. He’s an athlete. Because I understand some of the pitfalls in specialization, we have had him try everything. He’s done gymnastics, football, baseball, basketball, soccer and volleyball. The problem with our approach is, he doesn’t like most of them. He loves basketball and football. We have kept him in baseball because my wife’s family has deep ties to baseball, but it doesn’t motivate him. He loves basketball and football.

The reality: He’s nine years old and by his own hand has eliminated nearly all of the things he has tried, because there are only two sports that fire him up. I refuse to make him do something he hates.

At the ripe age of nine, my son swings kettlebells, does bodyweight exercise and even spent the summer doing speed training with my college athletes. He loves every minute of it. He is beginning to specialize, so Mom and I are exposing the idea to him that athletes, in the sports he loves, train. They lift weights . . . they run. He needs to know it’s part of the deal. Yes he has an advantage having a father who has made a career out of strength training, but herein lies the magic of this entire article.

They can specialize, at a very young age. And the second this begins, we as parents need to know that we have a new list of issues to combat. The best part is, the fix is an easy one.

Go out and hire a smart trainer. Your kid doesn’t have to be in the gym six days a week, but I would recommend one gym day/training session for every two days of practice.

My kids (nine, seven and five) all do something physical.

It’s not punishment, it’s simply a part of their day.

[afl_shortcode url=”http://www.otpbooks.com/product/dan-john-training-program-assessments/?ref=20″ product_id=’2618′]

[afl_shortcode url=”http://www.otpbooks.com/product/dan-john-chip-conrad-a-systems-approach-digital-video/?ref=20″ product_id=’2843′]

[afl_shortcode url=”http://www.otpbooks.com/product/developing-organizing-brijesh-patel-training-system/?ref=20″ product_id=’3957′]

[afl_shortcode url=”http://www.otpbooks.com/product/weight-training-for-high-school-athletics-zach-even-esh/?ref=20″ product_id=’3199′]

Interested in more volleyball-specific articles? These two injury prevention pieces from Greg Dea will keep you and your players healthy:

Bulletproofing the Volleyball Knee

Bulletproofing the Volleyball Shoulder

Tap into the Brains of Some of the World’s Leading Performance Experts

FREE Access to the OTP Vault

Inside the OTP Vault, you’ll find over 20 articles and videos from leading strength coaches, trainers and physical therapists such as Dan John, Gray Cook, Michael Boyle, Stuart McGill and Sue Falsone.

Click here to get FREE access to the On Target Publications vault and receive the latest relevant content to help you and your clients move and perform better.