Evan Osar: Developing and Maintaining Hip Mobility

Do you work with individuals who struggle with hip mobility despite your consistent efforts to help them find a solution?

I know how frustrating it can be to help your client develop hip mobility during their session, only to have her come back for her next session and find that her hips are as restricted as they were at her previous session. While many clients could be more proactive in their own self-care, I’ve seen many patients with chronically tight hips despite all the mobility work and self-care they do.

There are innumerous exercises and drills to develop hip mobility and you likely already have a strategy that serves your clients well. The challenge, therefore, is not in developing hip mobility, (so I apologize in advance if you are reading this article to discover the ‘secret’ or Holy Grail for improving hip mobility.)

As I see it, the more important component is in discovering a strategy that helps your client maintain the mobility you’ve helped them create.

The goal of this article is not to reinvent the wheel because, as mentioned, you likely already have an effective strategy for improving mobility. Nor is the intent to provide you with recipe that you will use with every single client. There are three primary goals of this article.

- Discuss three common and overlooked causes for the loss of hip mobility,

- Discover a three-part strategy for maintaining hip mobility, and

- Demonstrate how to integrate these concepts into the fundamental movement patterns.

Why do so many individuals lose hip mobility?

Three overlooked causes

As noted in the introduction, I believe there are three commonly overlooked causes for the loss of hip mobility.

1. Non-optimal three-dimensional breathing strategy

In recent years, breathing has replaced ‘core strengthening’ as the industry’s most current trend. While everyone seems to be discussing its importance as it relates to oxygenation or relaxation, few discussions include how breathing actually contributes to mobility and stability. There are three ways optimal and efficient breathing benefits hip mobility.

- Pressure regulation: Three-dimensional breathing regulates internal pressure thus stabilizing the trunk, spine, pelvis and hip complex and reducing the need for overusing a bracing or gripping (will discuss this term later in the article) strategy for stability. Non-optimal breathing (shallow and rapid) necessitates overactivity of the hip and core stabilizers for stability. Over time, this overactivity restricts both hip and thoracic mobility.

Using the entire thoracopelvic cylinder (trunk, spine, pelvis, and hip complex) in the breathing process mobilizes all the joints in these regions. As the individual breathes in, the ribs should expand, the spine should gently extend, and the pelvis should generally expand as well. Additionally, as the diaphragm descends, it mobilizes the internal organs which are fascially suspended within the thoracic, abdominal and pelvic cavities.

Shallow and rapid breathing does not incorporate use of the entire thoracopelvic cylinder and thus limits motion of the diaphragm. Additionally, the diaphragm tends to be positioned higher and moves less in individuals with chronic pain and those with failed back surgery syndrome (Bordoni et. al. 2016). I would add that flaring of the anterior portion of the rib cage and thoracolumbar hyperextension, tends to position the diaphragm higher in the front and restricts its posterior motion. With less diaphragmatic motion, there is less movement of the rib cage, spine, organs and pelvic floor which over time, limits both hip and thoracic mobility.

- Activation of the deep muscles including the psoas and pelvic floor: Optimal use of the diaphragm promotes optimal use of the core. The diaphragm, as part of the deep stabilization system, fascially connects to the psoas, transversus abdominus, and deep erector spinae. Additionally, as the diaphragm pushes the abdominal and pelvic organs inferiorly, it activates the pelvic floor which mobilizes the hips and maintains pelvic mobility.

Shallow and rapid breathing inhibits the diaphragm from fully descending and thus does not optimally activate the pelvic floor limiting organ, spine and hip mobility. Clinically, I have found improved core activation and subsequent improved hip mobility when the individual utilizes their entire thoracopelvic cylinder in the breathing process.

It is important to note that while it is common practice to use the terms belly breathing and diaphragmatic breathing interchangeably, they are not synonymous. Although an individual can perform belly breathing and use their diaphragm, they are not necessarily using it in an optimal or efficient manner. Three-dimensional breathing involves utilizing the entire thoracopelvic cylinder in the breathing process; superior-to-inferior (top-to-bottom), costal (side-to-side) as well as antero-posterior (front-to-back) (Osar 2017). This ensures the individual is able to access each region of their cylinder when required. Three-dimensional breathing supports the optimal position and use of the diaphragm and in turn, the optimal position and use of the diaphragm supports one’s ability to breathe three-dimensionally.

2. Over-activation of the posterior hip muscles (and corresponding fascial connections) during posture, daily activities and exercise.

The femoral head (ball) should remain relatively centered within the acetabulum (socket) during posture and movement (Lee 2012, Lee 2014, Sahrmann 2002). Note the relative optimal position of the hip (image A below). In individuals that present with chronic hip tightness, as well as individuals presenting with labral tears, FAI and/or hip osteoarthritis, it is common to find individuals over-gripping their posterior hip muscles and translating their femoral head excessively forward.

This strategy is referred to as ‘butt gripping’ (Lee 2012, Lee 2014) and anterior femoral glide syndrome (Sahrmann 2002). What’s frequently diagnosed as ‘gluteal amnesia’ is often over-gripping of the posterior hip muscles, (i.e. butt gripping). Butt gripping can involve over-activation of the gluteus maximus, gluteus medius and/or external hip rotators.

The picture above is of a 23-year old former collegiate baseball player who presented with a labral tear and sciatica. As is common in individuals with labral tears and degenerative changes of the hip, he presented with his femoral head positioned too far anteriorly in the acetabulum. A common sign that an individual is over-activating their lateral and/or posterior hip complex are the ‘divots’ (arrows in the image above) located in the lateral/posterior aspect of the hip complex. Note the schematic representation of the anterior femoral head position in image (B) above. This strategy also caused his pelvis to be posteriorly tilted reducing his lumbar lordosis thereby increasing the stress upon his lumbar discs and hence, sciatica. Although he required labral surgery, he returned after his post-surgical rehab and we worked on establishing more optimal control of his hip, pelvis and spine. Within two months, he had no sciatica and was able to fully return, pain-free, to his conditioning routine.

It is important to note a few of the more common causes of butt gripping as this strategy will directly contribute to one’s inability to maintain hip mobility.

- Habit: Many of us have been conditioned or taught to ‘squeeze’ our butt muscles or to ‘tighten our tushy’ for good posture. Additionally, most rehabilitation and conditioning strategies teach the individual to squeeze or tighten his/her butt to better activate the glutes at the end of the bridge, squat and deadlift patterns, for example.

Although this strategy may be initially warranted for creating awareness or for helping the client feel their glutes working, as alluded to previously, an over-reliance of this strategy will cause the individual to drive their pelvis too far into posterior tilt and positions the femoral head too far forward within the acetabulum (Lee 2012, Lee 2014, Sahrmann 2002, Osar 2017, 2018). This is the exact strategy that I believe is contributing to so many young athletes (even as young as 11 years of age) presenting to our clinic with chronic hip tightness, labral tears and FAI.

- Lumbar disc pathology and/or pain: Spinal pathology or pain can contribute to muscle inhibition (Lee 2014, Osar 2017) and atrophy of the spine, pelvis and hip stabilizers (Barker et. al. 2004, Dangaria et. al 1998, Kim 2011) and resultant over-activity of the posterior hip muscles as well as superficial trunk muscles (Lee 2012, Lee 2014, Osar 2017). This is a common strategy I find in virtually all my patients that have had spinal surgeries, including discectomies, laminectomies and/or fusions.

- Labral tears: The labrum is a fibrocartilaginous rim that aids stabilization of the femoral head within the socket. Just as a tear will not allow a suction cup to adhere to your shower wall, a tear in the labrum generally leads to instability and necessitates increased muscle activation around the hip. A common presentation in patients that present with MRI confirmation of a labral tear is clenching or gripping around their hip joint. The individual will frequently mention that he/she is unable to relax his/her hip flexors, adductors, and/or rotators because these muscles have become over-active in an attempt to support the torn labrum.

- For years, I suspected that excessive gripping was also a reflexive reaction for supporting the pelvic floor. This suspicion was confirmed by my colleague Dr. Judy Florendo, a specialist who regularly assesses and treats individuals with pelvic floor dysfunction including stress urinary incontinence (leakage of urine when coughing, sneezing or exercising). Dr. Florendo shared that it is common that individuals with urinary incontinence (UI) will over-activate their pelvic floor as well as their external hip rotators so that they don’t leak. Over time, this non-optimal strategy reduces mobility as well as decreases pelvic floor motion when breathing, hence perpetuating hip tightness.

Despite the belief that this is an issue only affecting older and post-partum women, studies show that a high percentage of female athletes also experience UI. The athletes with the greatest percentage of UI are runners, 45% (Poswiata et. al. 2014) as well as gymnasts and dancers, 56% and 43% respectively (Thyssen et. al. 2002). For individuals experiencing UI, it is often necessary to have them consult with a pelvic floor specialist.

What’s the issue with over-activation or gripping of the posterior hip muscles and/or pelvic floor? When individuals over-activate their posterior hip and/or pelvic floor muscles, they tend to excessively rotate their pelvis posteriorly. Chronically holding these muscles in shortened positions makes it difficult to eccentrically lengthen these muscles which is required when bending, squatting and lunging. This strategy leads to compensatory motion at the lumbar spine and/or knees and is one of the reasons I believe there is such a high incidence of issues in these regions.

Additionally, with chronic over-gripping of the posterior hip, the individual will tend to over-compress their hip joint disrupting the optimal resting position of both the hip and pelvis. Over-compression of the hip joint makes it increasingly challenging for individuals to release their hip muscles appropriately when they need to bend, squat, lunge or achieve many functional positions required for everyday life, including sitting.

Notice this individual sitting in posterior pelvic tilt. This is a common sitting posture in individuals with an over-compressed hip and/or short, tight posterior hip muscles. Over time, this position perpetuates shortness in the posterior hip muscles and flexes the low back (reversing the neutral lumbar lordosis) thereby increasing stress upon the discs of the lumbar spine.

3. Not respecting alignment and control of the trunk, spine, pelvis and hip complex during functional exercises.

Essentially this refers to using the appropriate exercise progressions and not progressing too quickly before developing the requisite mobility and/or stability to successfully perform higher-level progressions.

The following patient was referred to me because he was experiencing a recent onset of lateral hip pain. He was an advanced strength/conditioning coach and had been performing a regular hip mobility and dynamic warm up routine in addition to a high-intensity training program.

Note his alignment as I have him perform an Elevated Rear Leg Split Squat, a far easier exercise than he’s accustomed to performing. He demonstrates an inability to maintain alignment of his pelvis and hip and subsequently ‘dumps’ his pelvis in the frontal plane. By continuing to train in this way, his lower body exercise patterns will continue to reinforce this non-optimal stereotype and perpetuate his mobility issues and hip pain.

The Integrative Movement System™ Corrective Exercise Strategy

Before beginning any exercise program, you will want to have ruled out any underlying hip pathologies such as a labral tear or femoroacetabular impingement (FAI). It is up to you to do your due diligence and conduct a thorough history and assessment, use the most appropriate exercise and progressions and help your client successfully and safely work towards achieving their health and fitness goals.

In the Integrative Movement System™ Approach to Posture and Movement (Osar 2018), corrective exercise is part of an overall strategy for optimizing mobility and stability. After conducting a thorough history and assessment, the individual is progressed through the appropriate exercise progressions as well as home exercise program (HEP) so that he or she can develop his or her most optimal and efficient posture and movement strategy.

There are three specific components in the Integrative Movement System™ Corrective Exercise Strategy:

- Release: Release (manual or self-myofascial release (SFMR)) of myofascial restrictions, adhesions and/or regions of over-activation (gripping).

- Activation: Up-regulating the stabilizers and developing the appropriate level of co-activation or synergy between the prime movers and stabilizers required for maintaining optimal alignment and control (stability).

- Education: Using the most appropriate cues as well as the HEP to reinforce the mobility you are helping your clients develop.

Here is an example of using the Integrative Movement System™ Corrective Exercise Strategy to address the issues discussed in this article that contribute to hip tightness.

1. Release myofascial restrictions around the trunk, spine and hip complex.

While some individuals require release of their hip flexors and adductors, individuals stuck in posterior pelvic tilt (individuals who are butt grippers, who sit most of the day, and/or over-emphasize posterior chain strengthening), will generally need more release of their lateral and posterior hip musculature.

2. Train the ability to anteriorly rotate the pelvis.

As discussed, most individuals experiencing chronic hip mobility issues do not have an optimal strategy for anteriorly rotating their pelvis especially when bending, squatting or lunging. Over-activation (gripping) of the posterior hip complex and short hamstrings (secondary to prolonged sitting in posterior pelvic tilt) are two common reasons that explains why many individuals struggle to perform an optimal forward bend pattern or hip hinge. Additionally, this is one reason why they also have trouble achieving deeper squat, lunge and deadlift patterns.

Once you’ve had your client release his hips, perform the Hip Hinge progression to functionally lengthen his glutes and hamstrings. If you are unable to put your hands on your client, have him place his hands upon his pelvis to help you observe motion of his pelvis.

Additionally, this will help your client monitor his own pelvic motion and ensure he is creating pure anterior rotation and not compensating by flexing his lumbar spine. Progress the individual to the Split Stance and Elevated Rear Leg versions when appropriate.

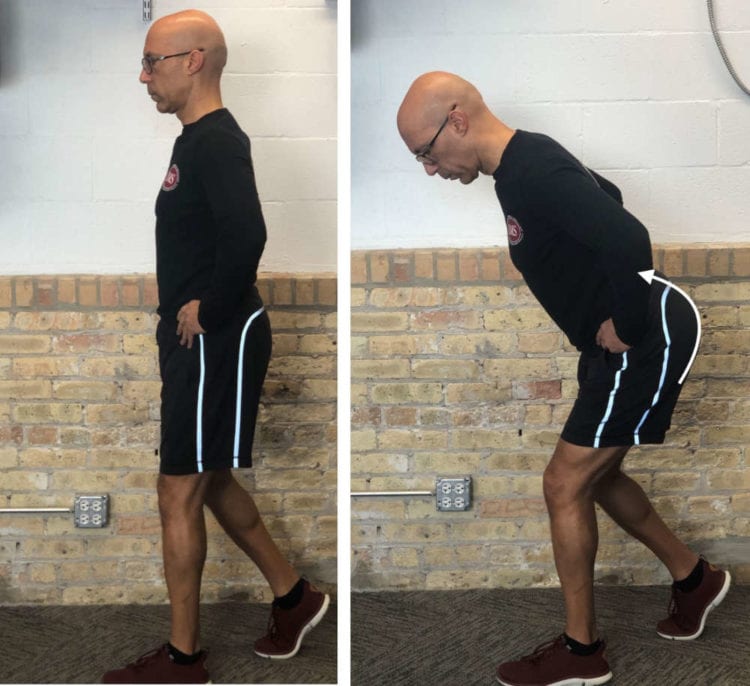

Regardless of the pattern – Squat, Lunge, Deadlift – the first motion of the pelvis should be anterior rotation (tilt) of the pelvis. Optimal anterior pelvic rotation (above left); non-optimal posterior pelvic rotation and compensatory lumbar spine flexion (above right).

3. Integration – Use the appropriate progression sequence.

While this may seem like common sense, note that common sense is not always common practice. Although it can be humbling to one’s ego, often times a regression is the most appropriate strategy so that the individual is able to develop the requisite mobility and/or stability necessary to progress to the higher-level progressions.

Split Squat Progression: Split Squat (front loaded) to Elevated Rear Leg Split Squat – Be sure your clients are able to achieve a minimum of 90-100° of pure hip flexion through anterior pelvic rotation before allowing them to progress into greater ranges of motion or more challenging progressions.

Naturally, you’ll progress your client’s patterns to include the frontal and transverse planes of motion. Regardless of the plane of motion or pattern being performed, be sure they are maintaining alignment and control of their trunk, spine, pelvis and hip complex so that they preserve the mobility you helped them develop.

Note: When deep squatting, optimal biomechanics requires that there is relative posterior pelvic rotation (tilt) and lumbar spine to relatively flex. However, most individuals should be able to readily achieve 90-100° of hip flexion (normal range of hip flexion is 120°) when squatting or bending before the pelvis begins to rotate posteriorly or the spine begins to flex. Inability to anteriorly rotate the pelvis due to butt gripping, lack of hamstring or external hip rotator length, hip joint capsule mobility, and/or non-optimal spinal stability are common causes of early and rapid posterior pelvic tilt (a.k.a. ‘butt wink’). Allowing an individual to perform patterns where there is early and rapid posterior pelvic rotation (tilt) and subsequent lumbar spine flexion is one of the most common perpetuators of hip mobility issues and contributors of lumbar disc injuries (Osar 2017,2018).

Click here for video demonstration of the concepts discussed in this article.

Conclusion

As mentioned in the onset of this article, there are many approaches to developing hip mobility yet far fewer available options for helping to maintain hip mobility once it’s been achieved. An important part of an overall strategy for maintaining optimal hip mobility is understanding what compromises it in the first place. Obvious origins of decreased hip mobility include the sedentary lifestyle and not enough emphasis on self-care. However, commonly overlooked causes that were highlighted in this article include non-optimal breathing strategies, over-activating the posterior hip complex and inappropriate exercise progressions.

Additionally, I discussed the importance of helping your

clients develop an optimal strategy for maintaining hip mobility and shared

with you how to use a corrective exercise strategy to optimize hip function. Your

assessment process will guide you to the regions that your clients most need to

release and activate as well as which are the most appropriate home exercises

your clients should be performing to facilitate the changes you are helping

them create. By performing a thorough assessment, using the most appropriate releases

and exercise progressions, and by developing an individualized home exercise

program, you can empower your clients to develop a strategy for developing and

maintaining hip mobility that helps them successfully and safely achieve their

health and fitness goals.

References:

Barker KL, Shamley DR, Jackson D. Changes in the cross-sectional area of multifidus and psoas in patients with unilateral back pain. Spine. 2004; 29(22):E515–519.

Bordoni, B., Marelli, F.: 2016. Failed back surgery syndrome: review and new hypothesis. Journal of Pain Research. 2016; 9:17-22.

Dangaria TR, Naesh O. Changes in cross-sectional area of psoas major muscle in unilateral sciatica caused by disc herniation. Spine. 1998; 23(8):928–931.

Kim, WH, Lee, SH, Lee, DY. Changes in the Cross-Sectional Area of Multifidus and Psoas in Unilateral Sciatic Caused by Lumbar Disc Herniation. Journal of Korean Neurosurgery Society. 2011; 50:201-204.

Lee, D. The Pelvic Girdle: An Approach to the Examination and Treatment of the Lumbopelvic-hip Region. 4th ed. 2012; Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh.

Lee, LJ. Advance Your Skills in The Thoracic Ring Approach & The Integrated Systems Model for Disability & Pain. 2014; Course handouts; Vancouver, BC.

Osar, E. Corrective Exercise Solutions to Common Hip and Shoulder Dysfunction. 2012; Lotus Publishing, Chinchester, UK.

Osar, E. The Integrative Movement Specialist Certification Program. 2018; Institute for Integrative Health and Fitness Education, Course handouts, Chicago, IL.

Osar, E. The Psoas Solution. 2017; Lotus Publishing, Chinchester, UK.

Poswiata, A., Socha, T., Opara, J. Prevalence of Stress Urinary Incontinence in Elite Female Endurance Athletes. Journal of Human Kinetics. 2014; 44:91-96.

Thyssen, HH., Clevin, L., Olesen, S., Lose, G. Urinary incontinence in elite female athletes and dancers. International Urogynecological Journal of Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2002; 13(1):15-7.

Sahrmann, S. Diagnosis and Treatment of Movement Impairment Syndromes. 2002; Mosby, St. Louis, MO.

Tap into the Brains of Some of the World’s Leading Performance Experts

FREE Access to the OTP Vault

Inside the OTP Vault, you’ll find over 20 articles and videos from leading strength coaches, trainers and physical therapists such as Dan John, Gray Cook, Michael Boyle, Stuart McGill and Sue Falsone.

Click here to get FREE access to the On Target Publications vault and receive the latest relevant content to help you and your clients move and perform better.